The animal history of the

Greenland shark in the waters

around Iceland

Author:

Dr. Dalrún Kaldakvísl, animal historian

Greenland shark conservation

Icelanders must protect the ocean if it is to protect them. As the famous 19th-century shark hunter Sæmund Sæmundsson (1869-1958) once said after nearly losing his sons to the sea, "Perhaps the ocean believes I have taken too much from it without giving it anything in return except for fish blood and sweat."

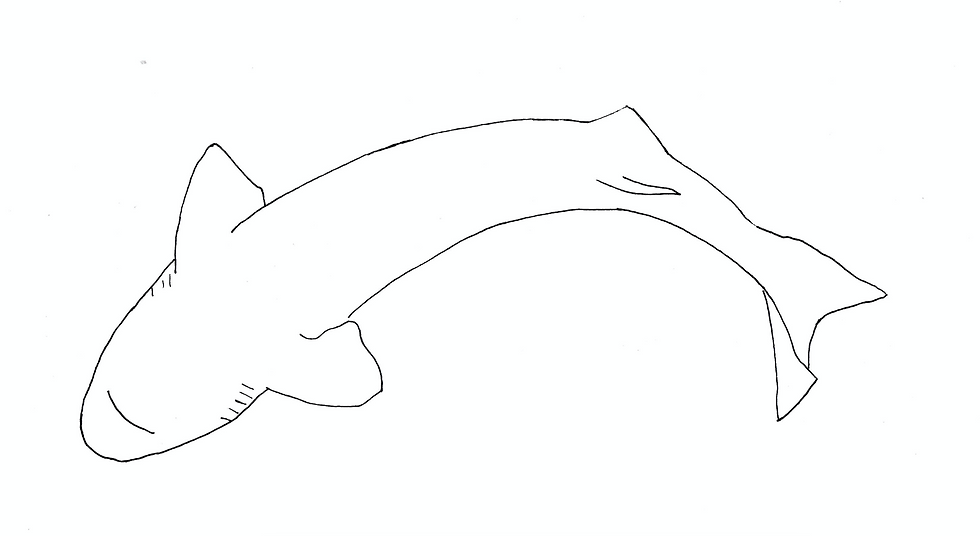

Climate research shows that the ocean and its biodiversity are crucial for the health of the Earth’s atmosphere. The Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus / ice. hákarl) is the longest-lived vertebrate on Earth, reaching hundreds of years in age and growing many meters in length. As a top predator in the North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans, the shark plays a significant role in discussions about ocean health. Scientists estimate that shark populations have declined by 30-49% over the past 450 years, primarily due to historical oil exploitation. Although there has been an estimated 3% population growth over the past century, shark populations remain vulnerable to overfishing because of their slow growth rate and late sexual maturity—typically, they do not reach sexual maturity until around 156 years of age. Shark offspring develop inside the mother and are born alive after a gestation period of approximately 8-18 years. A single female shark can give birth to up to ten live young, emphasizing the importance of each individual and highlighting the urgent need for conservation action.

Scientists have also identified increasing threats to Greenland sharks due to climate change. It is predicted that 50% of the Arctic ice will melt over the next 100 years, allowing fishing fleets greater access to the northernmost oceans, which is expected to have a devastating effect on shark populations. Target Greenland shark fishing is rare today and therefore probably has little impact on the size of the shark population. The same cannot be said for shark bycatch, however. Today, sharks are primarily caught as bycatch in trawling operations for other fish species, which has a significant impact on the decline of their population. Scientists estimate that approximately 3500 Greenland sharks are unintentionally caught as bycatch annually in the Northwest Atlantic, Arctic Ocean, and Barents Sea. These numbers are possibly higher regarding unrecorded bycatch and discards. In my interview with a fisherman who has worked on Icelandic bottom trawlers, he spoke about how common it was to catch and discard Greenland sharks in the Greenland Sea: "Last time we caught between 40-50 sharks as bycatch – that is usual." Bottom trawling—a destructive fishing technique—also severely harms the seabed and has long been detrimental to shark habitats. Furthermore, shark fishing, whether direct or indirect, disrupts the carbon cycle by removing large, long-lived organisms from the ocean, thereby altering the balance of the carbon cycle. These organisms capture carbon in significant quantities, and without them, much of this carbon will not reach the seabed to dissolve over time.

According to the Icelandic Fisheries Agency, there are currently no specific regulations governing shark fishing, whether for traditional shark hunting or as bycatch. This stands in contrast to the protections afforded to specific shark species in Iceland’s fishing zone, such as the basking shark, the porbeagle shark, and the spiny dogfish. Today, the Greenland shark is in such a dire state globally that it is classified as a vulnerable species by the IUCN. In 2022, the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization (NAFO) banned shark fishing in international waters, but countries like Iceland, which prohibit discarding bycatch, may be exempt from these regulations. There has been a significant and growing domestic opposition to whaling among the Icelandic public in the late 20th century and 21st century, echoing global anti-whaling demonstrations. Despite widespread international protests against shark hunting, the Icelandic populace remains indifferent to the practice in their own country – fishing Greenland sharks is not a contentious issue in Iceland, whether intentionally targeted or incidentally caught. Aside from ingrained speciesism, the lack of concern for shark fishing in the late 20th and 21st centuries, compared to the increasing concerns among the Icelandic public against whaling, stems from the fact that shark fishing is a fundamental aspect of Icelandic hunting culture and national identity. In contrast, whaling does not have deep historical roots in Iceland, as foreign nations primarily carried it out in Icelandic waters until the mid-20th century.

Shark hunting has been a longstanding part of Icelandic cultural identity, reflected in both our food culture and museum culture. This image has seen a revival with the increase in tourism to the country. While it is essential to preserve and pass on the history of shark hunting, we must also protect the natural environment on which that history is based. Greenland sharks are particularly vulnerable due to their slow growth and late sexual maturity, which means that gaps in their population can have a significant impact on recruitment. The extensive hunting of sharks by Icelanders and other nations from the 17th century to the mid-20th century has had a lasting effect on their population status. Today, climate change and trawling pose the most significant risks.

The historical bond between Icelanders and the Greenland shark is truly unique on a global scale. Because of this, Iceland is well-positioned to take the lead in safeguarding our ancient companion from bycatch, drawing on our rich history, knowledge, and connections. Icelanders must commit to safeguarding Greenland sharks. We owe a debt to these ancient creatures, which provided vital sustenance to our ancestors during times of great need. However, modern Icelanders no longer need to seek protein in the wild, especially not from the world's longest-lived vertebrate, which reaches sexual maturity after 156 years and accumulates harmful mercury over its lifetime. It is more important than ever for Iceland, once a shark-fishing nation, to become a champion of shark conservation, benefiting not only the sharks but also the ocean and future generations.

May the historic Icelandic shark-fishing nation become a shark conservation nation in the future for the benefit of the shark, the ocean, and future generations.

Shark fishing in Iceland

It is believed that shark fishing has been practiced in Iceland since the country's early settlement. Both men and women caught sharks using hand lines, bait lines, and weights. They also fished for sharks through the ice when the sea ice broke off and washed ashore. For many years, Icelanders have utilized shark flesh as food and extracted the liver oil from sharks. The 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries marked a significant turning point in shark fishing history, as hunters began targeting sharks primarily for their oil. During this time, shark oil became a valuable export due to high demand abroad; the fat from the shark's liver was used to illuminate foreign cities until kerosene became widely used, leading to a decline in the need for shark oil. This era can be likened to an "oil rush" for the people of Iceland —a time when Icelandic shark hunters brought up large quantities of the Greenland shark, the source of light from the dark depths of the sea. Thus, the Greenland shark and its oil certainly played a role in the Industrial Revolution outside the mainland.

For centuries, Greenland sharks were seldom mentioned in Icelandic historical records. When they were referenced, the focus was primarily on their byproducts, especially the meat. It wasn't until the Icelandic public began to document their experiences in greater detail that sharks started making a more regular appearance in the historical narrative. This shift is particularly evident in the memoirs of sailors who participated in shark fishing during the 19th century. These writings aimed to capture and preserve the fishing techniques that have since faded into obscurity, as historical shark fishing typically took place from rowboats and shark schooners. In one notable book, Sharks and Sharkmen, the author and shark fisherman Theódór Friðriksson (1876-1948) describes the recollections of sharkmen, noting "a peculiar hunting spirit, distinctive men, and a peculiar time – considerable toughness, but no less bravery and manliness." Analysis of these accounts reveals the extreme conditions faced by Icelandic shark fishermen who navigated the perilous deep to catch sharks. Shark hunting was among the most dangerous and gruesome forms of fishing in 19th-century Iceland. Sharkmen, as shark fishermen were most often called, would frequently venture far into the shark grounds, spending days or even weeks at sea, depending on the success of their catch. Fishermen, usually farmers and farm laborers, typically went shark fishing during the winter and spring months. One shark fisherman recounted that “it was not suitable for cowards to do this work in the dead of winter on open ships; there was no shelter from storms and snow or any form of heating.” Sharkmen had to endure harsh weather, including strong winds, freezing temperatures, sleet, and often battled with sea ice. A seasoned shark fisherman once remarked, “Shark fishing was tough and chilling.” Conditions on shark-fishing vessels were frequently poor, with no shelter from the elements and no opportunity for rest, as the constant risk of cold exposure made it difficult to sleep. Improvements came with the introduction of schooners, which offered cabin spaces and better facilities for heating coffee and food. Nevertheless, reports of poor hygiene on shark boats were common, with the stench of rotting shark liver permeating the air, exacerbated by the sharkmen's indifference to cleanliness. The perilous nature of shark fishing is reflected in the numerous accounts of shark ships lost at sea, with tales of entire crews disappearing and the tragic consequences for their families, leaving women widowed and children without fathers. The experiences of the sharkmen highlighted resilience and endurance as their most essential qualities. Traditionally, their seafaring skills were often linked to masculinity, and the abilities of sharkmen were frequently regarded with greater reverence than those of other male occupations in Iceland, both on land and at sea—a high masculinity that could be described as “sharkinity” (hákarlmennska).

Traditionally, shark fishing was male-dominated, with men primarily responsible for fishing. However, historical records show that women were also engaged in the shark fishing industry. Women such as Jófríður Hansdóttir (1818-1885), who bore a child on a shark fishing expedition, or women such as Steinunn Árnadóttir (1852-1933), who ensured herself a spot on her father's shark ship by showcasing her physical strength: “She lifted the heaviest stone on the seashore.”

Modern Greenland shark fishing in the 20th and 21st centuries primarily focuses on obtaining shark meat for human consumption, particularly for Iceland’s Þorrablót festival. Meanwhile, the practice of shark fishing for oil has almost disappeared; discussions with local fishermen indicate that fish oil producers in Iceland typically source their oil from overseas instead of utilizing the local shark oil that remains available. The dynamic between shark fishermen and their catches underwent a significant transformation with the advent of motorboats. In interviews conducted by the author, Dalrún Kaldakvísl, with fishermen involved in this practice, it became clear that this shift has reduced the direct interaction between fishermen and the sharks compared to earlier times. Nowadays, fishermen set lines that are checked only after one or two days, leading to less immediate engagement with nature. Direct shark fishing is quite rare today, and very few fishermen take up this activity as a side endeavor. In the era of motorboats, shark fishers were often referred to as "free fishing" within the quota system.

Ríkharð, a shark fisherman and meat processor:

“Everywhere else in the world, sharks are known for eating people, but here in Iceland, we eat sharks. It’s thrilling!”. The mystique surrounding sharks has been amplified in films, adding to their allure. When children are out at sea with their dads on a trawler, you can hear them eagerly asking, “Have you caught any sharks?” The excitement is palpable. Bringing the sharks back to the pier was always a delightful experience, drawing crowds of people who gathered to see the Greenland shark.

(interview | Kalda)

Sigurbjörn Sæmundsson, shark fisherman

Sæmundur Sæmundsson

Jóhann Magnússon & Björn Ólafur Jónsson, shark fishermen

Theódór Friðriksson, shark fisherman and writer

Haukur Jóhannesson, descendant of shark fishermen

Hreinn Björgvinsson, shark fisherman

Björgvin Agnar Hreinsson, shark fisherman

Sverrir Björnsson, shark fisherman

Lúðvík Ríkharð Jónsson, shark processor

Gísli Konráðsson, shark processor

Relationship

The Greenland shark holds an important place in Icelandic culture as a resource, but less so as a living creature. Historically, the shark's role in Icelandic folklore, fiction, and history has been minimal. Therefore, the experiences of Icelandic shark hunters are particularly valuable for understanding Greenland sharks as living beings and the relationship between Icelanders and this ancient being. These historical accounts reflect the rare memories of men and women who have encountered living sharks in the sea. The perspectives of seafarers in Iceland over the centuries provide scholars with an opportunity to explore and enrich the connection that Icelanders have with their surrounding seas and ecosystems. The memories of shark hunters testify to a relationship between humans and fish that spans from the ocean surface to its depths. This relationship was primarily based on fishing. Icelandic shark hunters had to learn and pass on knowledge about the Greenland shark's behavior and movements to locate it in the deep waters of Iceland. They had to know how to lure the shark onto the hand line hooks and recognize its behavior once it was hooked. The myriad names used for sharks in the past reflect the shark hunters' profound understanding of these creatures, taking into account factors such as gender, sexual maturity, size, and length.

To gain a clearer picture of the shark hunters' relationship with Greenland sharks over a century ago, envision a shark hunter clad in fur clothing and a sea jacket, rowing through the cold darkness of the night alongside his companions in a rowboat anchored by the captain. Equipped with Iceland's oldest shark-fishing gear, a hand-held line/hook (ice. vaður), the shark hunter lowers the line into the depths, holding it loosely over the deck as he patiently waits for a shark to nibble the bait. This process usually took many hours. During these long, quiet waits, shark hunters often passed the time by reciting rhymes and verses. This leads us to an intriguing aspect of the shark-fishing tradition: the verses recited/sung by the shark hunters while they waited. With these verses, they were effectively addressing the shark, using their words to lure the creature onto the hook. The fact that humans address sharks for fishing purposes is a very rare occurrence worldwide. A rare example of this unique relationship can be found in specific island communities in Papua New Guinea, where fishermen call sharks to their canoes so they can spear them. Additionally, Icelandic shark poetry/verses offer a glimpse into the emotions of hunters as they wait, filled with anticipation and excitement, for a Greenland shark to take the bait. These verses also incorporate humor, reflecting the hunters' feigned sympathy for the creatures they ultimately plan to catch.

Poor shark, listen to me,

you are down below,

I extend food to thee,

how glad you should be.

The delicate movements of the hunters and the shark's cautious approach were the prelude to the chaos that ensued when the shark nibbled on the bait. It was then hoisted from the depths, a hook driven into its jaw, and dragged along the deck before being cut up. Often, the men would only remove the liver to extract fish oil, discarding the shark's carcass into the sea. This act attracted other sharks to the ship, even drawing them to the surface. The shark men witnessed these predatory sharks moving freely across the water's surface, often in large numbers, with a sole intention: feasting on their deceased comrades. Consequently, the shark men would frequently pull them to the surface. Historical shark fishing is a pretty brutal practice, completely lacking regard for the shark's well-being. The creatures were usually stabbed and cut open alive to remove their livers before being released, leading to their inevitable sinking and death. The historical practice of fishing for shark oil evokes the controversial shark finning methods still employed by some foreign nations today. In these cases, only the fins are removed, leaving the sharks to be tossed back into the ocean, where they suffer a slow and painful death.

Shark hunters showed little compassion for their catch. In their memoirs, they often portrayed the sharks as adversaries, framing their encounters as conflicts or battles with the enemy. They even referred to their fishing gear as a form of weaponry. When faced with many Greenland sharks coming up to the surface whilst eating their dead comrades in the surface —what the shark men called a "mad shark"—the men sometimes claimed they themselves became semi-savage, going berserk on board during the hunt. They admitted to being driven by their primal instincts. To illustrate the ferocity of the shark men, here is a description of a sharkman's encounter with "fighting" many Greenland sharks who had come up from the deep:

The ship is roaring and creaking. We've caught a big one. After a little while, the shark appears shackled in iron. But Mister Grey wants to protect himself and manages to escape from the hands of his enemies. Now, he opens his mouth and clamps down on the hook, already submerged in his jaw, causing a cracking sound. – During the transition from high to low tide in the early morning, Mister Grey fought tirelessly, keeping everyone busy. "Quickly, pass me the harpoon," one seaman called out to the captain. It was accomplished swiftly. He aimed the harpoon into the deep until it struck a giant shark. "Old Tough" lurked below, devouring his fallen comrades. It was a mistake; if we could harpoon or hook him, his demise was inevitable. It was a full-blooded battle at daybreak.

(Jens Hermannsson, „Hákarlalegur: Frásögn Hermanns Jónssonar skipstjóra“)

It was not uncommon for sharkmen to personify sharks, attributing human characteristics to them. This tendency is not surprising, considering that sailors in earlier centuries often anthropomorphized natural phenomena, particularly those they had to confront, such as sea ice. In sharkmen's accounts from the 19th century, sharks were often referred to in Icelandic masculine terms, such as the traditional word hákarl "sharkman", and gamli gráni and háskerðingur. However, in earlier times, sharks were sometimes personified as feminine, referred to as hákerling "shark-woman." The historical sharkmen's attitude towards Greenland sharks as living beings is characterized by its paradoxical nature. On one hand, they demonstrated a certain respect for sharks, acknowledging them not only as adversaries but also as formidable predators, noting their size, strength, sharp teeth, and exceptional sense of smell. On the other hand, shark enthusiasts often described sharks as sluggish, weak, lazy, ugly, dull, lethargic, and submissive when caught. There was a perception that sharks were very picky eaters, which led to significant effort being put into preparing bait; for example, it was common to fill seal pups used as bait with rum to increase the smell of the bait. This practice sometimes gave rise to humor, as it was joked that the Greenland shark was considered a drunkard, for he was greedy for rum. Shark enthusiasts viewed the main weakness of sharks as their tendency to be greedy, which made them easy prey. The shark hunters' attitude towards the shark reflects the well-known attitude towards predators, that the shark is justly killed because it feeds on the ocean's resources and shows no mercy in its hunt; the loner who eats its kind. The shark's reputation for greed also influenced its image as a predator. A 19th-century shark hunter observed that Icelandic fishermen cursed and scolded sharks more frequently than other fish, as sharks often became entangled in their fishing gear, causing damage. He wrote:

I have seen many fish caught from the sea and am familiar with most of the species commonly found in Icelandic waters. However, I have never heard fishermen direct such unkind words towards at any fish as those aimed at the Greenland shark. For a long time, sailors in the north had a habit of cursing this fish in the sand and ashes whenever its name was mentioned. Even the shark hunters, who often put in a great deal of effort to catch these sharks, would express their frustrations in the same way, although perhaps not always with genuine malice. In northern Iceland, the Greenland shark was the most vital fish, playing a crucial role in saving people from starvation during times of famine and hardship. (Jón Dúason)

This text presents a compelling example of how people's attitudes toward the Greenland shark can conflict when it is considered both as an organism and as a product. The shark, as a predator, embodies a particular ferocity, while as a source of meat and oil, it represents a crucial resource for Icelanders.

Interestingly, 19th-century shark fishermen were often described by themselves and by their peers in ways that mirrored the descriptions of the Greenland shark. The shark fishermen were portrayed as alien, primitive, peculiar, and even archaic figures, living on the fringes of society, either in shark fishing huts or at sea. Shark fishermen were frequently portrayed as the trolls of the ocean: exceptionally strong and valiant individuals who tested their strength against the forces of nature—the cold, the sea, the wind, the icebergs, and the "old grey," referring to the Greenland shark. They often engaged in competitions at sea, pitting their hunting skills against one another, or wrestled onshore in their free time. Shark fishermen were also reputed to have incredible capacities for consuming alcohol, shark oil, coffee, and food. Similarly, the Greenland shark itself was depicted as a large, primitive, ancient, savage, and wild creature, driven by its hunting instinct and lacking restraint. It was even jestingly claimed that the shark was a drunkard, having consumed rum-soaked seals, which were once considered excellent bait. Consequently, the Greenland shark does not seem like an alien creature in these shark-hunting tales; instead, it appears to be a reflection of the shark hunters themselves, out at sea, perhaps even a model of their own essence.

Modern shark fishing often appears harsh, showing little concern for the sharks' well-being. These creatures can be left on hooks for days, suffering in silence. During my conversations with contemporary shark fishermen, I found a stark lack of empathy towards sharks. They viewed them as merely another type of fish. For them, this disregard was just part of the experience—the anguish felt distant, much like the shark itself, lurking in the depths. Views towards Greenland sharks caught as bycatch indicate they are seen as a nuisance, as they frequently become entangled in fishing gear and damage it. One interviewee of mine, a fisherman who worked on a traditional fishing vessel, recounted, "We were fishing for halibut in the Barents Sea when a big shark got tangled in the line—that's why we were only getting halibut heads. So we used large shark hooks to catch those robbers —the sharks—they were just like the bird, the northern fulmar, in our eyes. We caught seven sharks." This sailor, who worked on a longline boat, described the shark as looking "half dead" when brought to the surface, resembling a carcass. However, he also expressed sympathy for the killer whales that fed on the hooks when the crew caught them on the same trip, stating, "It hit one, but they broke the line afterward—killer whales are so intelligent."

The relationship between humans and fish is inherently different from that between humans and land animals or marine mammals. People find it much easier to connect with marine mammals than with fish. They also tend to personify marine mammals based on their appearances and sounds; for instance, animals like whales and seals are often described as beautiful and majestic. In contrast, sharks rarely receive such accolades. One modern shark hunter remarked, "I have experienced being in a school of whales that included minke whales, dolphins, killer whales, and humpback whales, which are all majestic animals of the sea." Greenland sharks typically dwell in deeper waters, ranging from 100 to 1,200 meters, which makes them difficult to observe directly. One shark fisherman mentioned, "Of course, you don’t see a Greenland shark wading like a basking shark." In the past, sharks were often caught on handheld hooks, making them more visible when alive. Historical fishermen would sometimes throw sharks back into the sea after taking their livers, which led to other sharks coming to the surface to feast around the boats. Modern shark fishermen seldom encounter free-roaming Greenland sharks, but on rare occasions, they do. On these occasions, these elusive creatures are typically seen just beneath the surface, shadowing a caught shark that's being pulled in. One interviewee shared, "Yes, I’ve witnessed it more than once—seeing a shark following a shark that is being hauled in. You could see it clearly, but there was no fuss; it was just there, slowly following the carcass." The attitude of shark hunters towards these creatures is influenced mainly by their treatment of sharks as products. As they process the sharks, they become more aware of various aspects of the sharks’ ecology and nature, including their sex and the contents of their stomachs, which reveal their eating habits and provide insight into the behavior of the animals they prey upon. It was fascinating to observe the extent of understanding the shark hunters had regarding shark behavior through these interactions. As they worked on the sharks, they noted the variety and often large size of the prey the sharks had consumed, which underscored these predators' capabilities. Awe was evident in the hunters' voices as they dissected the shark's remains and spoke about its prey, which provided evidence of its hunting abilities.

The Icelandic shark hunting history revolves around the relationship between the shark and Icelandic shark fishermen, but other animals, both underwater, above water, and on land, are also intertwined with this history. This includes the animals used as shark bait, such as seals, horses, and porpoises, et cetera. In addition, there were the animals that the shark fishermen encountered during the hunt, such as the northern fulmar, which often tried to snatch the shark's liver from the hunters' hands, or the lice on the shark's scales that announced its arrival from the deep sea. The shark's animal story also concerns the animals that the shark eats, which come to light when the shark fishermen cut open the shark's stomach: seals, cod, catfish, halibut, skate, porpoise, squid, crab, jellyfish, seabirds, and even salmon and whales. The animal story also spans the process of fermentation, where bacterial flora comes to life, until the shark meat is finally hung up, and then the arch-enemy of sharks, the fly, comes into play. Even the polar bear is part of Iceland's shark story, as tales tell of polar bears making their way into a fragrant shark meat drying den by the ocean shore, and other stories recount when farmers used shark-hunting tools as weapons against polar bears – and in 1973, a shark hunter discovered a polar bear cub inside a shark's stomach.

A news clip from 1898 reporting the drowning of a Norwegian whaler in western Iceland. He fell off a boat and was believed to have been eaten by a shark after screaming for help and sinking into the depths.

The Greenland shark has never been documented as eating humans, although Icelandic folklore suggests that red-haired children or elderly women were considered effective bait for these creatures.

Shark meat

In historian Lúðvík Kristjánsson's masterpiece, Íslenskir sjávarhættir [Icelandic Custom at Sea], it is noted that the Greenland shark has over 90 names in Iceland, highlighting its significant role in Icelandic fishing culture. Only the cod has more names, according to Lúðvík. This abundance of names reflects the unique place that sharks hold in Icelandic fishing traditions. For centuries, the people of Iceland have preserved their knowledge about Greenland shark fishing and shark meat processing, as seen in the writings of folklorists and historians and the preservation of shark fishing culture in the Shark Museum in Bjarnarhöfn, the Shark-Jörund House in Hrísey, and the preservation of the shark ship Ófeigur at the Reykjavik Regional Museum. The Greenland shark has been used in several ways, including as a source of food (its meat, cartilage, and eggs), for lighting (its liver), and even for shoemaking with its scales. Even though sources indicate that Icelanders experimented with processing basking sharks for liver oil, as was a common practice among the Irish, it was not at all a known procedure—Icelanders primarily caught the Greenland shark for liver oil. The consumption of fermented Greenland shark meat has historically contributed to Iceland's image as an exotic island nation, even though Icelanders rarely eat shark today, doing so primarily during Þorrablót, a midwinter festival. Since target fishing for the Greenland shark has become increasingly rare in Iceland. Instead, it is more common for non-fishing shark processors to buy frozen Greenland shark meat from trawlers that accidentally catch Greenland sharks as bycatch. My conversations with shark meat processors who buy frozen shark meat from Icelandic commercial fisheries reveal that they usually lack firsthand knowledge of the Greenland shark as an organism, as the shark is cut and frozen before reaching them.

The Greenland shark frequently appears in Icelandic historical and fictional accounts, primarily as a source of meat, and thus is regularly seen by locals as food rather than a living creature, as is often the case with fish. This perspective shapes people's attitudes toward fish as food rather than as living beings (the "Icelandic term hákarl refers to the Greenland shark, both as a type of organism and as a food). Fermented shark meat appear in numerous paradoxical forms throughout Icelandic history, acting as food for the poor, a symbol of primitive culture, a vital resource during hard times, an ancient food source, a potentially toxic food item (when eaten fresh), currency, a national dish, a thrift food, and even a medicinal item: "Shark is good for women with milk in their breasts," noted a shark fishermen in a newspaper interview from 1972.

The Greenland shark symbolizes the slow passage of time. It is a slow-growing fish that moves gently through the depths of the ocean and takes a long time to hunt and to be processed into food. The traditional method of preparing shark meat involves a process that has remained essentially unchanged for centuries. Shark processing begins with catching the shark, cutting up the meat, and leaving it in the sand and/or gravel/rocks on the beach for several weeks or longer. Fermentation occurs as microorganisms prevent spoilage, allowing high levels of trimethylamine oxide (TMAO) to gradually leach from the meat, making it safe to consume. Shark hunters and processors of the 20th and 21st centuries continued to use the same traditional methods as their ancestors. However, instead of burying the shark high on the shoreline, modern hunters ferment the meat in perforated wooden boxes or plastic containers. “It’s a dirty job – you always come home smelling of ammonia,” commented one shark hunter during my interview. The consensus among my interviewees, who were shark hunters and processors, was that shark processing is particularly messy, often accompanied by the pungent odor that lingers during the curing process. They frequently spoke of the meat they processed as if it were alive, which makes sense considering that the shark meat transforms during fermentation due to the remarkable microbial interactions involved. After the shark has been fermented, it is cut into strips and hung in an airy shark shed to dry for several weeks or months. This process—whether curing or drying—ensures that the shark remains edible for an extended period. A familiar theme in Icelandic folklore is that the older the shark, the better it tastes – something that contemporary shark processors dispute, pointing out that the flesh begins to deteriorate at a certain point. However, folk tales suggest that a well-processed shark can age indefinitely. Another myth related to the shark's function and its age in product form revolves around the virtue of urinating on the shark while it is being processed.

The long shelf life of processed shark, alongside the changing flavors as the product ages, has contributed to its mythic status as a living entity in Icelandic literature and culture. The fermented shark takes on a life of its own in Icelandic culture, often featuring in stories in the form of a "twelve-year-old shark," which is frequently mentioned in Icelandic folklore. The fermented shark meat carries an air of mystery. It is believed to hold magical powers, fitting seamlessly into the enchanting world of Icelandic fairytales, where creatures like trolls are often imagined to feast upon it. The mystery of the shark as a product also builds on the mystery surrounding the shark's existence as a living organism, and even when it is dead, as there are many legends about how long the shark moves after it has been slaughtered and brought ashore.

Although the popularity of fermented shark has waned among younger generations, it has found renewed interest in the growing tourism industry, where eating the meat becomes a ritual centered on the diners' reactions. Shark meat is often paired with an Icelandic alcoholic alcohol known as brennivín/black death, which shark hunters historically consumed to keep warm out at sea. Eating mature shark is considered a masculine act, influenced by the distinct taste of the meat, the male image of the shark, and cultural notions of masculinity associated with shark hunting. Both traditional and modern Icelandic beliefs emphasize the notion that consuming shark meat and liver oil can enhance men's physical strength. Additionally, some sources suggest that eating shark may improve male sexual potency. Interestingly, shark products are also tied to concepts of femininity. For example, old ideas indicated that women should apply fish oil to their hair to make it thicker, and there were beliefs that shark consumption could support women’s milk production, as well as that of sheep and cows. Despite reports of the nutritional and healing properties of sharks, such as their use in treating stomach ailments, scientific studies indicate that consuming long-lived sharks can be risky due to their high mercury content.

For more information, visit Dalrún's writings about the history of sharks in Iceland